Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes (1914)

Translator's Note: This is a machine-assisted translation completed on May 19, 2025. While care has been taken to maintain accuracy, this translation has not yet undergone human review or validation. Please note that specialized terms, historical references, and nuanced content may benefit from expert review.

In this comprehensive scholarly volume, Magnus Hirschfeld in 1914 sought to compile all available knowledge about homosexuality between two covers. In the sections on Norway, Bergen was particularly emphasized.

With Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes, the German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld (1868–1935) provided a more comprehensive introduction to the subject than anyone had done before. Eighteen years earlier, as a young physician, he had published the short pamphlet Sappho und Sokrates (1896), in which he outlined the foundations of his theory that homosexuality was an innate characteristic that could be explained scientifically and biologically, but was not a disease. While this understanding is widespread today, in Hirschfeld’s time it was a radical new idea that challenged prevailing conceptions.

The year after publishing the pamphlet, Hirschfeld founded the first organized European movement advocating for greater acceptance of those belonging to this minority group: the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. Hirschfeld identified as homosexual—or “Uranian,” as he also termed it—but this was not something he disclosed publicly. Instead, he cultivated his persona as a scientist. Science, particularly the natural sciences, was his weapon of choice, and since 1899 the Committee had published the Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen (Yearbook for Sexual Intermediaries), featuring scholarly articles on what Hirschfeld, using an umbrella term, called “sexual intermediaries”: individuals who, biologically, deviated markedly from the typically masculine or typically feminine. (For Hirschfeld, gender was a spectrum, not a binary.) In addition to homosexuals, these sexual intermediaries also included other groups, among them “transvestites”—a term Hirschfeld himself coined, roughly corresponding to what we today understand as transgender individuals.

While Sappho und Sokrates had been a modest 35 pages, with Die Homosexualität, Hirschfeld produced the most extensive sexological study on the subject to date. The book spanned over a thousand pages and was described by a British sexologist as the most detailed, precise, and exhaustive work on the topic thus far—“an encyclopedia of homosexuality.”[1] This vast body of material was intended to support the theory that homosexuality was a biological, innate trait (see e.g. Marhoefer 2022, pp. 41–43). The evidence was drawn not only from biology and medicine, but equally from history, geography, and ethnography. The book is densely packed with accounts of homosexuality and gender nonconformity from across the globe, and this serves a clear purpose: the presence of same-sex desire in all times and places, among a minority of people (2–3 percent), was for Hirschfeld proof of the theory that homosexuality was both biological and natural.

The sources for these geographical and ethnographic descriptions were partly literature Hirschfeld had read himself, and partly stories and anecdotes he had gathered from his informants—often men he knew through his homosexual network.

“A Well-Traveled Uranian” in Bergen

In Die Homosexualität, Hirschfeld takes the reader on a scholarly journey around the world in search of homosexuality, and along the way, he also addresses the situation in Norway. He observed that homosexuality did not appear to be particularly widespread in the country, but added:

“Experts and specialists, however, also observe more here, and one of my informants, a well-traveled Uranian, tells me that, based on his experiences and observations, Bergen is the most homosexual city in the world” (Hirschfeld 1914, p. 534).[2]

We do not know who this informant was—it may have been a German from Hirschfeld’s circle who had happened to visit Bergen, or perhaps a Norwegian acquaintance (such as the Bergen native Justus Lockwood, who is known to have been part of Hirschfeld’s network in Germany).

Hirschfeld replied to his informant that it was indeed interesting that Bergen was the site of the first known legal prohibition against sex between men (in the 12th century, under the Gulating Law). He also noted that other Old Norse sources indicated that homosexuality had been widespread among the ancient Norse. This was supported by an article published in the Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen in 1902, written anonymously by “a learned Norwegian.”

As a source, the account of Bergen is primarily to be regarded as a curiosity. Nevertheless, it at least suggests that a homosexual man had experienced certain possibilities in Bergen—perhaps referring to public meeting places, which are known to have existed in the city during the first half of the twentieth century (such as parks and public urinals), to male prostitution, or to networks of men who engaged in sexual relations with other men.

Furthermore, the passage indicates that Hirschfeld possessed some knowledge of the situation in Norway, at the very least through the article he published in his Jahrbuch in 1902. It is likely that he was aware that the “learned Norwegian” who authored the article was the former professor and later National Archivist, Ebbe Hertzberg (1847–1912). Whether Hertzberg had direct contact with Hirschfeld remains unknown, but he was acquainted with several individuals within Hirschfeld’s network (Jordåen 2022, p. 20).

Natural, Not Decadent

The well-traveled Uranian’s claim regarding the particularly widespread presence of homosexuality in Bergen somewhat contradicted Hirschfeld’s main thesis—namely, that homosexuality, as a biological phenomenon, did not vary according to geography or ethnicity. Hirschfeld was especially opposed to a prevailing notion of the time: the idea that homosexuality was a product of decadence, degeneration, and “over-civilization,” typically associated with large cities and modern societies (Marhoefer 2022, pp. 45–46).

Hirschfeld also had a Finnish informant, a jurist, who provided information about the people living in the northern part of the Scandinavian Peninsula—the Sámi (“Die Lappen”), “who constitute a distinct nation.” Among them, homosexuality was also said to be widespread, and the Finnish informant had been told that this was connected to certain religious practices.

According to contemporary views on ethnic groups and degrees of civilization, the Sámi were likely regarded as the opposite of decadent, feeble, and “over-cultivated” urbanites. Thus, the claim of homosexuality among an “indigenous people” could serve to support Hirschfeld’s central thesis.

Given the likely assumptions of his readers—that certain ethnic groups were superior to others—it was probably an even more persuasive argument for Hirschfeld to emphasize that homosexuality was, as he stressed, well known among “the certainly not degenerate North Germanic peoples and Vikings” (Hirschfeld 1914, p. 535). Homosexuality, in other words, was equally prevalent in cultures that could in no way be perceived as marked by decadence or decline.

Scholars such as Heike Bauer and Laurie Marhoefer have shown that although Hirschfeld opposed scientific and biological racism, and later also imperialism, his work was nonetheless shaped in part by the dominant colonial-era notions of higher and lower cultures (Bauer 2017; Marhoefer 2022). As a Jewish German, he was himself subjected to racism and antisemitism, and became a frequent target of hatred from the extreme right.

Hirschfeld and Norway

While another explorer of the human psyche and sexuality, Sigmund Freud, gained a number of dedicated followers in Norway, Hirschfeld’s direct influence was more limited. At the same time, he has been a far more well-known figure than previously assumed—something Stian Hårstad has thoroughly documented in an article based on coverage in the Norwegian press (Hårstad 2020). Among other things, Hårstad shows that the looting of Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin and the burning of much of its material during the infamous Nazi book burning in 1933 were described in considerable detail in Norwegian newspapers. The coverage ranged from strongly critical portrayals of the book burning (e.g., in Bergens Arbeiderblad, 13 May) to overtly antisemitic and anti-homosexual characterizations in Buskerud Blad (Hårstad 2020, p. 11).

See also: Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson supported Hirschfeld’s appeal for decriminalization in Germany.

At the time his institute was looted, Hirschfeld was already in exile, and a few years later he died in Nice, France.

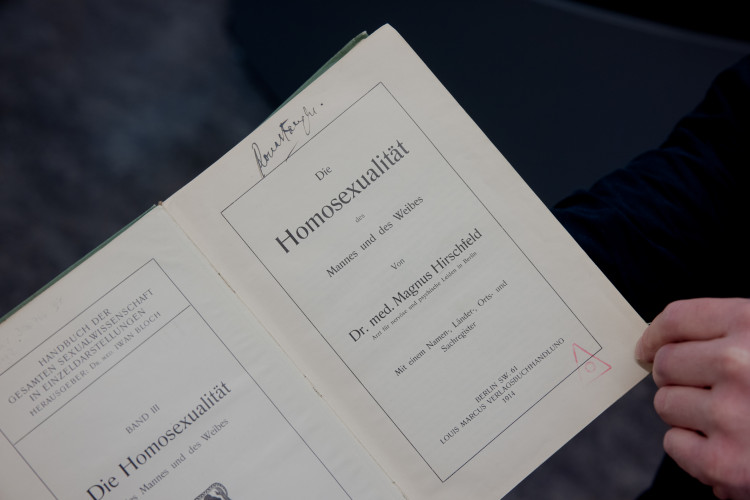

The Signature

That Hirschfeld’s writings were known even among Norwegian intellectuals with same-sex desires is suggested by the copy of Die Homosexualität held by the Norwegian Queer Archive (Skeivt arkiv). The book bears the signature of the author Ronald Fangen (see facsimile of the title page at the top of the article). In his youth, Fangen was for a time part of a network of homosexual men in Kristiania (Roughtvedt 2007). He also addressed the topic in his early novels, albeit in a language more pathologizing than that of Hirschfeld.

Notes

[1] Havelock Ellis in Studies in the Psychology of Sex (3rd edition, 1915), cited by Hirschfeld in “Vorwort zur Zweiten Auflage” (Preface to the Second Edition) (Hirschfeld 1920, p. XIV).

[2] Hirschfeld 1914, p. 534. “Experts and specialists, however, also perceive more here, and one of my informants, a well-traveled Uranian, reports to me that, based on his experiences and observations, Bergen is the most homosexual city in the world.”

[3] “In the northern parts of the Scandinavian Peninsula and Finland live the Lapps, who constitute a distinct nation. Among them, homosexuality is also said to be very widespread, and it is reportedly connected to religious practices (Hirschfeld 1914, p. 539).”

References

Bauer, Heike. The Hirschfeld Archives: Violence, Death, and Modern Queer Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017.

Hirschfeld, Magnus. Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes. Berlin: Louis Marcus Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1914.

Hirschfeld, Magnus. Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes. 2nd ed. Berlin: Louis Marcus Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1920.

Hårstad, Stian. “The Gay Pioneer Magnus Hirschfeld in Norwegian Newspapers in the First Half of the 20th Century.” Skeivt arkiv, 2020. Accessed October 4, 2022.

Jordåen, Runar. “Introduction.” In ‘De har brudt isen her i Norden’. Brev til Poul Andræ 1892–1912, by Ebbe Hertzberg, 10–36. NB Sources 13. Edited by Runar Jordåen. Oslo: National Library of Norway, 2022.

Marhoefer, Laurie. Racism and the Making of Gay Rights: A Sexologist, His Student, and the Empire of Queer Love. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2022.

Roughtvedt, Bernt. Riverton: Sven Elvestad og hans samtid. Oslo: Cappelen, 2007.