The Leaflet Campaign 'Homosexual at Blindern' in 1967

Translator's Note: This is a machine-assisted translation completed on May 14, 2025. While care has been taken to maintain accuracy, this translation has not yet undergone human review or validation. Please note that specialized terms, historical references, and nuanced content may benefit from expert review.

In April 1967, the newspaper Dagbladet reported on a leaflet campaign carried out at Blindern, under the subheading “probably several hundred with a homosexuality problem.” One year before the student uprising in Paris, and two years before Stonewall, two Oslo students dared to distribute leaflets addressed “to the homosexual student.”

The Stonewall riots at the Stonewall Inn in New York are often considered the beginning of the modern radical gay rights movement. In that year, 1969, homosexuality between men was still illegal in Norway (Section 213 of the Penal Code).

There were no rights or protections against discrimination for queer people, and it’s easy to assume that Norwegian queer activists didn’t come out or demonstrate openly until after Stonewall—or even after the decriminalization of homosexuality in 1972.

But during the decade leading up to the Stonewall uprising, significant changes had already taken place in how the Norwegian gay movement operated and lived.

Emerging Activism

Kim Friele often spoke about the difficulties of meeting other gay people when she arrived in Oslo in the early 1960s. She sat on a bench day after day, week after week, month after month.

When she finally gained access to the organization The Norwegian League of 1948 after two years, it was a group with a code name (“The Association for Town and Country”), entry only for pre-approved members, and strict confidentiality requirements.

Activism was a far cry from Stonewall and open street revolution.

In 1965, things slowly began to change. A sign of what was to come was the first Norwegian gay magazine available for public sale, OSS, published by the League.

That same year, the first Norwegian radio program about homosexuality aired, featuring two real—though anonymous—gay men in the studio.

Arne Heli, a former chairman of DNF-48, also gave a speech at a packed meeting of the Student Society on homosexuality, using the pseudonym Ivar Selholm.

The League’s internal magazine, Oss imellom, wrote: “It’s as if we, who have lived in darkness for so long, can now glimpse a faint ray of light in the distance” (Oss imellom 2-65).

The First Queer Student Demonstration

But change takes time. Two years later, no one in Norway had yet come out publicly with their full name.

What the newspapers wrote about homosexuality was usually anonymous letters to the editor or varying discussions of “the homosexual problem.”

But in 1967, the first queer student demonstration took place at Blindern.

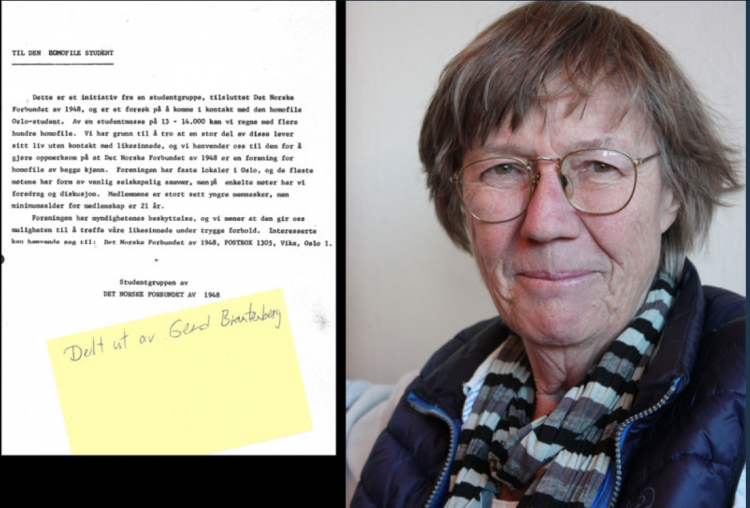

Gerd Brantenberg, who would later become known as the author of Opp alle jordens homofile! (Rise Up, All the World’s Homosexuals!) and a voice for the lesbian women’s movement, had missed having a forum for gay students at the university.

In Løvetann 3-98, Brantenberg recounts how she, along with a gay fellow student referred to as A (identified as Anners in Klubbnytt 2-67), approached University Director Trovik to ask for permission to distribute a leaflet addressed “to the homosexual student.”

Regarding their approach, Brantenberg said, “We did it this way because homosexual relations between men were still illegal.”

The leaflet also stated that “the association is protected by the authorities, and we believe it gives us the opportunity to meet like-minded people in safe conditions.”

Even though Section 213 was rarely enforced at that time, it still carried symbolic weight and created a real fear of prosecution among queer Norwegians.

As Løvetann wrote in 1998, this “first visible student lesbian/gay demonstration” came a year early—that is, a year before the student uprisings of 1968.

And even though student environments are often radical, this was not about openly handing out leaflets:

“A. went ahead – with a flat cap pulled low over his head, a large parka with the collar up over his ears, and I wore a raincoat, sou’wester, and rubber boots. We had hidden the stacks of leaflets under our coats. I saw A. quickly toss a stack onto a table while glancing around (...). We even dared to hang one leaflet on the bulletin board. It was very nerve-wracking. But no one noticed us. We left the building with our hearts pounding.”

Ripple Effects

This first queer student demonstration—innocent and cautious as it may seem today—had ripple effects. The League’s internal newsletter, Klubbnytt, wrote in May 1967 that “the campaign has resulted in countless inquiries; in one day alone, no fewer than 12 inquiries were received.”

The campaign was also mentioned in the League’s magazine OSS in the June 1967 issue. There, the two students were described as “a board member of DNF, editorial member of OSS” (OSS, 1967, p. 23).

And not only that—the leftist student newspaper Epoke reached out and published an interview with the two activists.

The student newspaper’s editor, Egil Ulateig, described meeting A. like this:

“A strong, handsome young man. I look for feminine traits in him. But even his interests are those of an ordinary young man: cars, technology, music, outdoor work.”

According to Brantenberg, homosexuality was an “absolute non-topic” among students at Blindern. Perhaps that explains Ulateig’s stereotypical expectations. He also emphasized how “normal” Brantenberg appeared.

News Value

The campaign also had news value beyond Oslo’s student community: Dagbladet covered the campaign on April 22, including interviews with the two students. Both interviews were anonymous.

Even so, the activists were met with a wave of gratitude and enthusiasm when they showed up at the League the following Saturday. “They thought we had been incredibly brave,” Brantenberg wrote 30 years later.

Despite a budding openness in the gay movement, despite the early fight against Section 213, despite a gay magazine being sold publicly and a League advocating for gay rights, it was still almost unheard of to take action in this way.

Dagbladet wrote: “Whether [the campaign] can be taken as a sign of greater societal interest in these issues is hard to say.”

As we know, society’s interest in “these issues” fortunately grew significantly in the years that followed.

From 1968–69 onward, and especially after the repeal of Section 213 in 1972, the Norwegian gay movement became more open, gained greater visibility in public consciousness, and visible demonstrations became the new norm.