Legal Protection for homosexuals

Translator's Note: This is a machine-assisted translation completed on May 16, 2025. While care has been taken to maintain accuracy, this translation has not yet undergone human review or validation. Please note that specialized terms, historical references, and nuanced content may benefit from expert review.

"Særskilt strafferettslig vern for homofile" - specific legal protection under criminal law for persons of homosexual orientation.

On April 21, 1972, Section 213 of the Penal Code, which prohibited sexual acts between men, was repealed. Decades of tireless advocacy by the Norwegian National Association for Lesbian and Gay Liberation (DNF-48) finally bore fruit. The decriminalization of homosexual acts opened new doors for the queer movement; gradually, gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people became more visible, stepping out from secret clubs and private spaces into the public eye. However, this newfound visibility also brought increased vulnerability. Despite the legal change, hatred and prejudice against homosexuals remained deeply rooted in society. DNF-48 experienced a growing number of reports concerning discrimination, abuse, and physical violence.

The repeal of Section 213 was a crucial milestone, but it was not enough: removing criminal penalties alone could not change societal attitudes. DNF-48 therefore advocated for amendments to Sections 135a and 349a of the Penal Code, so that these would also cover discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Anti-Discrimination Legislation

Sections 135a and 349a of the Norwegian Penal Code were introduced in 1970. These legal provisions originated from a 1965 UN resolution calling for the elimination of all forms of racial discrimination. Section 135a belongs to Chapter 13 of the Penal Code: "Crimes Against Public Order and Peace." At the time, it read as follows:

“Anyone who, by public statement or other communication disseminated among the general public, threatens, insults, or incites hatred, persecution, or contempt against a group of people based on their religion, race, skin color, or national or ethnic origin, shall be punished with fines or imprisonment for up to two years. The same penalty applies to anyone who encourages or otherwise contributes to such acts.”

Section 349a, part of Chapter 35: “Misdemeanors Against Public Order and Peace,” stated:

“Anyone who, in a commercial or similar activity, denies a person goods or services on the same terms as others due to their religion, race, skin color, or national or ethnic origin, shall be punished with fines or imprisonment for up to two months. The same applies to anyone who, for such reasons, denies a person access to a public performance, exhibition, or other public gathering on the same terms as others.”

DNF-48 believed that expanding these sections of the Penal Code to also include discrimination based on sexual orientation would be highly significant. The organization’s then Secretary General, Karen-Christine Friele, expressed it this way:

“These criminal provisions would make it easier to counter prejudice and would have an educational effect. In particular, legal protection for homosexuals would boost their self-esteem and reduce much of the secrecy and fear. More people would come out and live life on their own terms. Those who were already open would gain the legal protection they were entitled to.” (Friele 1990: 247)

The Political Process Begins

In a letter dated June 12, 1974, DNF-48, represented by Chairman Martin Strømme and Secretary General Karen-Christine Friele, addressed then Minister of Justice Inger Louise Valle (Labour Party).

In the letter, they acknowledged the importance of the repeal of Section 213 of the Penal Code, but shifted focus to the experiences that followed: the previously hidden antipathy toward homosexuals had evolved into open and ruthless discrimination against those who lived openly. They emphasized that the situation was untenable and that concrete measures were necessary:

“The Association finds it not only necessary but self-evident that the Minister of Justice should help put an end to the discrimination homosexuals are currently subjected to. One way to actively contribute to this is to ensure that the current Sections 135a and 349a of the Penal Code are amended to include that discrimination based on sexual orientation is not permitted.”

DNF-48 requested a meeting with the Minister of Justice, specifically asking for it to take place on June 27, Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day: “This celebration of the will of homosexuals to fight for their basic rights is observed in many countries. A conversation with you is one of several ways we have chosen to mark the day.”

Justice Minister Inger Louise Valle responded positively to the request. During the meeting, DNF-48 presented the minister with a detailed written account of the situation, including numerous concrete examples. The first examples concerned incidents in nightlife venues—spaces where emotions, flirting, and physical contact are typically expected and accepted forms of interaction.

In August 1973, a gay couple dancing together was told they were unwelcome at the nightclub Excellent in Bergen. A police prosecutor told the newspaper Morgenavisen: “Restaurants can refuse to let homosexuals dance together. They are no longer criminals, but that doesn’t mean they can expose themselves if others don’t like it.” In Oslo, two women dancing together at the venue Key-House were subjected to severe physical violence by a security guard, who, according to the victims, justified his actions by saying “they were making out so badly that the guests reacted.” The incident was reported to the police but was dismissed without further investigation, as it was deemed “insignificant.”

The next example involved the Church of Norway. From the pulpit in Vennesla Church on March 11, 1973, Pastor Nils Møll declared: “It’s not called homosexuality, but homomania. Mania means madness. Homosexuals are insane.” DNF-48 reported the statements to the Bishop of Agder, but received a delayed and evasive response from a bishop who stated he would not take a position until he had “informed himself about how far the church had come in addressing this issue.” (“The Homosexuality Question”).

DNF-48 also pointed to educational materials used in schools and institutions that they believed conveyed a prejudiced, intolerant, and false view of homosexuality. Finally, they highlighted the military’s regulations, which in principle deemed homosexuals unfit for service, based on the notion that homosexuality was a disease.

The Penal Code Council’s Recommendation

Justice Minister Inger Louise Valle took DNF-48’s request seriously. In February 1975, she tasked the Penal Code Council with considering whether homosexuals should be granted specific legal protection against unlawful discrimination. The council consisted of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Rolv Ryssdal, Professor of Law Dr. Johs. Andenæs, Supreme Court Attorney Else Bugge Fougner, and Associate Professor of Medicine Dr. Berthold Grünfeld. Their first meeting was held on December 13, 1975.

However, the council’s work took time. The official report NOU 1979:46 – Special Criminal Protection for Homosexuals was not submitted to the Ministry of Justice and the Police until four years later, on July 28, 1979. The recommendation was divided: Else Bugge Fougner and Berthold Grünfeld supported special legal protection for homosexuals, while the council’s permanent members, Rolv Ryssdal and Johs. Andenæs, opposed it.

The arguments against expanding the anti-discrimination law centered on concerns that it would restrict freedom of speech. Opponents believed that education and awareness were the appropriate tools—not the threat of punishment. “We do not promote tolerance by criminalizing certain opinions,” stated Member of Parliament Georg Apenes (Conservative Party), who was also a former chair of the Norwegian Press Complaints Commission. (Friele 1990: 261)

DNF-48’s Secretary General Kim Friele expressed her frustration in a letter to Wenche Lowzow:

“The two permanent members of the Penal Code Council believe that the means to combat discrimination against minority groups must fundamentally differ depending on the group in question. For racial and ethnic minorities, it is reasonable to combat discrimination through legislation. For homosexuals, however, laws are deemed inappropriate because they might offend people and create division.” (SKA-0001, Friele: Eg.1 folder 3)

The report NOU 1979:46 also noted that there had only been two final convictions under the then-current Section 135a of the Penal Code. One involved the so-called Hoaas case, in which a teacher made anti-Semitic remarks during class; the other concerned racist graffiti.

The issue of discrimination against homosexuals—and the question of special legal protection—sparked widespread public debate. Both experts and ordinary citizens were deeply engaged, as reflected in numerous newspaper articles from the time. While letters to the editor often questioned whether homosexuality was acceptable at all, politicians and professionals debated the merits of legal protection. MP Sveinung O. Flaaten (Conservative Party) summarized the dilemma:

“When deciding on legal protection, one must weigh freedom of speech on one hand against the rights of those subjected to severe abuse on the other. It is a matter of one human right versus another. One must yield.”

However, DNF-48 disagreed that expanding the anti-discrimination provisions threatened freedom of speech, repeatedly pointing out:

“If an expanded Section 135a violates the constitutional right to free expression, then isn’t the entire section unconstitutional?” (Friele 1990: 262)

Since DNF-48 first contacted Justice Minister Inger Louise Valle in the summer of 1974, there had been two changes in the ministerial post. From 1980 to 1981, Oddvar Berrefjord (Labour Party) served as Minister of Justice. In the autumn of 1980, he and the government proposed introducing special legal protection for homosexuals by expanding Sections 135a and 349a. In a press release, the government referred to the two cases that had resulted in convictions under the Penal Code’s anti-discrimination provisions (cf. NOU 1979:46). It was emphasized that violations would need to be particularly egregious to result in conviction, and that the expansion would not conflict with freedom of speech. Regarding concerns that such a legal change might provoke increased hostility toward homosexuals, the government stressed that homosexuals themselves were calling for this protection.

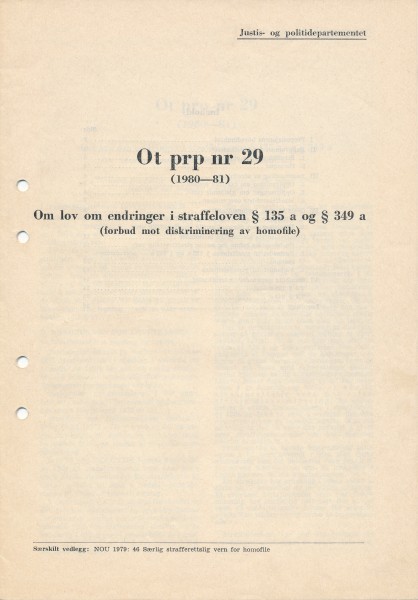

On January 16, 1981, the Ministry of Justice and the Police presented Ot.prp. nr. 29 (1980–81) – On Amendments to Sections 135a and 349a of the Penal Code (Prohibition of Discrimination Against Homosexuals). On March 17, the Justice Committee issued its recommendation on the same provisions.

For Section 135a, first paragraph, the following addition was proposed:

“The same applies to such offenses committed against a person or group on the basis of their homosexual orientation, lifestyle, or identity.”

And for Section 349a, first paragraph:

“The same penalty applies to anyone who, in such business activity, denies a person goods or services as mentioned, due to their homosexual orientation, lifestyle, or identity.”

The law was passed with a large majority in both chambers of Parliament—Odelstinget on April 7 and Lagtinget on April 24, 1981. With this, seven years of tireless advocacy by DNF-48 culminated in victory. Kim Friele describes the moment in her memoir:

“I have no clear memory of everything that happened later that day. But a couple of hours are etched in my mind—those Wenche and I had the pleasure of spending in the garden with Inger Louise Valle. It was the first time in my life I had the joy of being hugged by a government minister—and she was absolutely in her right mind!” (Friele 1990: 266)

After the Legal Changes

DNF-48 actively utilized the new anti-discrimination legislation and, in the years that followed, reported numerous cases involving discrimination, harassment, and denial of services based on sexual orientation. Among these was the so-called Bratterud case from 1984, in which Pastor Hans Bratterud of the Oslo Full Gospel Church was reported for violating Section 135a due to hateful statements broadcast on the radio. Documents concerning this and many other discrimination cases can be found in Kim Friele’s archive at the Queer Archive.

In 1985, Member of Parliament Jørgen Sønstebø (Christian Democratic Party) proposed repealing the amendments to Sections 135a and 349a of the Penal Code. This proposal was not supported by the Justice Committee.

Protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation was later incorporated into both the Equality Act and the Working Environment Act. However, certain exceptions were made: these concerned “internal matters within religious communities” (Equality Act) and “differential treatment based on homosexual cohabitation in employment for positions related to religious communities” (Working Environment Act).

On January 1, 2014, a new law came into force: the Act on the Prohibition of Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Gender Expression (Anti-Discrimination Act on Sexual Orientation). The prohibition applies to discrimination based on “actual, assumed, former, or future sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression” (Section 5, first paragraph). However, exceptions still exist: differential treatment is not considered a violation of the prohibition when it has “a legitimate aim,” is “necessary to achieve that aim,” and there is “a reasonable relationship between the aim pursued and the impact on the person or persons disadvantaged” (Section 6: Lawful Differential Treatment).

The current Working Environment Act (Section 13.1.7) directly refers to the Anti-Discrimination Act on Sexual Orientation: “In cases of discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression, the Anti-Discrimination Act on Sexual Orientation applies.” Section 13.3 provides an exception, now in a more generalized form and no longer specifically mentioning “homosexual cohabitation”: differential treatment that has “a legitimate aim, is not disproportionately intrusive to the person or persons affected, and is necessary for the performance of work or profession” is not considered discrimination under the law.

Since 1980, work has been ongoing to develop a new Penal Code for Norway. The new Penal Code is being introduced in two stages: the new general part was adopted in 2005, and the proposal for the special part (containing specific criminal provisions) was presented in 2008. However, full implementation of the law requires coordination with other legislation, and outdated IT systems within the police have been a bottleneck in this process. The current government has set a goal for the new Penal Code to come into force on October 1, 2015. The existing Sections 135a and 349a will then be replaced by the new Sections 185 (Hate Speech) and 186 (Discrimination).

Materials related to anti-discrimination legislation in Norway and the LGBTQ+ movement’s efforts to amend and expand it can be found in SKA/A-0001, Karen-Christine Friele’s archive, and SKA/A-0003, Gro Lindstad’s archive at the Queer Archive.

Sources:

Universitetsbiblioteket i Bergen. Skeivt arkiv. SKA/A-0001, Karen-Christine Frieles arkiv.

Friele, Karen-Christine. 1990. Troll skal temmes. Oslo: Scanbok

Diskrimineringsloven om seksuell orientering. Lov om forbud mot diskriminering på grunn av seksuell orientering, kjønnsidentitet og kjønnsuttrykk av 21. juni 2013 nr. 58. https://lovdata.no/dokument/LTI/lov/2013-06-21-58

Arbeidsmiljøloven. Lov om arbeidsmiljø, arbeidstid og stillingsvern. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2005-06-17-62

Store norske leksikon. “Diskriminerende ytringer”, lest 27. mars 2015, https://snl.no/diskriminerende_ytringer

Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet. "Lov om ikraftsetting av straffeloven 2005 (straffelovens ikraftsettingslov)". Prop. 64 L (2014-2015). Oslo: Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet, 2015. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/prop.-64-l-2014-2015/id2399784/

Straffeloven. Lov om straff av 20. mai 2005, nr 28. "Annen del. De straffbare handlingene. Kapittel 20. Vern av den offentlige ro, orden og sikkerhet". (Kapitlet tilføyd ved lov 7 mars 2008 nr. 4, men ikke satt i kraft). https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2005-05-20-28/KAPITTEL_2-5#%C2%A7185