"Tvitoling" and "båing": Gender Transgression in Norwegian Language History

Translator's Note: This is a machine-assisted translation completed on May 16, 2025. While care has been taken to maintain accuracy, this translation has not yet undergone human review or validation. Please note that specialized terms, historical references, and nuanced content may benefit from expert review.

This article was first published in the third issue of the queer cultural magazine Melk, which came out in 2017. This is a lightly revised version.

Language history offers valuable insights into how gender and sexuality have been understood over time. Concepts such as tvitoling and båing are examples of this.

Traces of queer history in Norway are scattered and difficult to find before the mid-20th century. Priests, lawyers, and authors often preferred not to elaborate on concrete transgressions of gender and sexuality norms, fearing that merely speaking about the taboo could be harmful. Still, the traces are there, well hidden in court records and other archival materials. Court cases where men were convicted for sex with other men are an important type of source, and they can often provide a fascinating glimpse into lived lives, identities, and past ways of thinking.

A few years ago, when I was looking more closely at such a case, a word appeared that I had previously only barely known. The case concerned a 65-year-old baker who was convicted for sexual relations with men in the 1890s in Porsgrunn. The case also referred to an incident a few years earlier:

Once, in Skien, he was accused of being a Tvetulling, which was written on a piece of cardboard that was hung up [...] and as a result, he was approached by several men.

(SAK: Porsgrunn City Court, preliminary hearing protocol 1, folio 60b.)

This passage is interesting for several reasons: the term tvetulling seems to have been a familiar concept both to the judge and to the population of Skien at the end of the 19th century. When someone put up a note saying that the person was a tvetulling, it clearly resulted in him being approached by a number of men. From this, we might infer that people in Porsgrunn understood a tvetulling to be someone who was available for advances from men.

But what kind of word is this? Should the passage be interpreted to mean that it is synonymous with “homosexual man”? The term homosexuality had just been introduced into the Norwegian language at this time, but it was hardly well known outside of small circles, and as far as we know, it had only appeared in print in psychiatric textbooks and medical journals (Jordåen 2010: 89). If we are to believe this source, however, tvetulling was such a well-known term that notes about it could be posted in the streets of a Norwegian town and be interpreted in a specific way.

The court case from Porsgrunn doesn’t provide much more to go on regarding the meaning and use of the word. But it inspired me to further investigate how this term has been used.

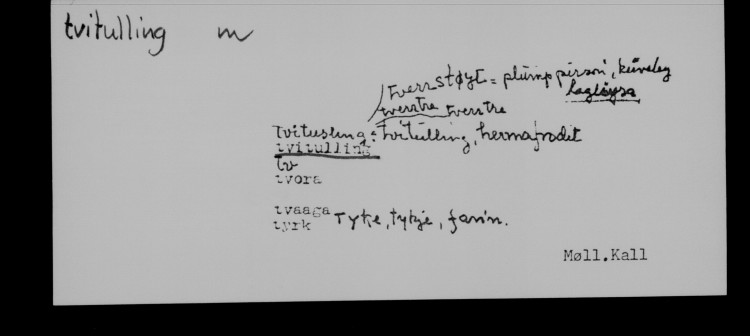

Tvitulling in Literature and Folk Speech

If we turn to written language, we find that the word has not merely been a local slur. The Ordbog over det danske sprog (Dictionary of the Danish Language) is a comprehensive historical dictionary of Danish and the shared Danish-Norwegian written language. There, we find the entry tvetulle and its derivatives (tvetulling, tvetullet). From this, it appears that the word has been used in Swedish (tvatola), Norwegian (tvitola, tvitoling), Icelandic (tvítóli, tvítólingur), Low German (tweetuler), and North Frisian (twitule).

The origin of the word is tvi (two, double) and Old Norse tól (tool, cf. English tool). According to the dictionary, the meaning is “hermaphrodite; sometimes derogatory, about an effeminate man.” Additionally, the word has been used figuratively—to describe something that is neither one thing nor the other.

An example of the literal meaning can be found in Holberg’s Moral Thoughts:

“It has until now been believed that shellfish were tvetuller.”

In the journal Kiøbenhavnske nye Tidender om lærde og curieuse Sager from 1762, one finds the sentence:

“Albertus Magnus claimed to have seen tvetuller who could perform and complete the functions of both sexes.”

A sentence from Georg Brandes’ book Michelangelo Buonarroti (1921) shows a usage of the word that also implies same-sex desire or homosexuality:

“The tvetullede trait in not a few of Leonardo’s paintings recalls a certain period in antiquity’s fondness for the blending of male and female characteristics in Bacchus.”

(This and the quotes above are taken from the Ordbog over det danske sprog, under the entry “Tvetulle.”)

The figurative meaning appears in many places in both Danish and Norwegian literature, for example in Arne Garborg:

“Yes, yes. I was a man from a middle ground. So one becomes a middle ground oneself. Unlucky; broken; incoherent. And nationally a tvitoling; both Danish-Norwegian and Norwegian. So one becomes nothing whole. A middle ground.” (Garborg 1925, p. 88)

The term has thus had a wide distribution in the Nordic countries and northern Germany. And as the examples show, it has been used quite a bit in literary language. Full-text searches in the National Library also show that it appears in Norwegian fiction, including in texts by Knut Hamsun, Kristoffer Uppdal, and Jens Bjørneboe (Hamsun 1930: 170, 191; Uppdal 1919: 15; Bjørneboe 1974: 47).

Norsk Ordbok is a comprehensive dictionary of Nynorsk and Norwegian dialects. According to it, tvitulling or tvitoling is often used to describe “intersex” or “sexless” animals, especially goats and hens that do not lay eggs. Additionally, there are instances where it is used about humans. In the source material for the dictionary, it is also used as a slur against people. In one case, it is explained as “half man and half woman” (information from Lars Vikør, Norsk Ordbok, email correspondence with the author).

The term also appears in many local dialect dictionaries. For example, in Kvam in Hardanger, it is explained as “a physically abnormally developed person” (Kvam kulturminnelag 1993: 37). In Voss, the form tvitutling was also used, and in a glossary of the Voss dialect, it is explained as “intersex individual, hermaphrodite” (Røthe 1994: 153–154).

Even in more recent times, the term has been used. A woman born in 1927 who grew up in rural Hordaland, for example, recalled from her youth several men who behaved “effeminately,” especially when they had been drinking. These were called tvitullingar (Kristiansen 2008: 52).

Hørve, Kværkje, and Båing

The search for the spread and use of the term tvitulling also led me to other words and expressions. The Nynorsk Etymological Dictionary contains several words with roughly the same meaning. One is hørve, which is explained as “hermaphroditism.” Another is kværkje, a word related to korkje (meaning “neither”), and defined as “poor, awkward creature, tvetulle.” Finally, there is baading or båing (Torp 1919: 239 and 355).

A closer look at the last term shows that it had relatively wide usage in central Norway. In Norsk Ordbok, the word is defined as “a person who is both sexes; tvitoling, hermaphrodite” (Hellevik 1966: 1219). In the dictionary’s slip archive, there is documentation of the word from all over Trøndelag, with various pronunciations (e.g., boing, båing, båeng). It is also found in Os in Østerdalen (as noted in an email from Olaf Almennigen to the author, 17.06.2015).

The term has also left musical traces in the form of the tune Båingen from Verdal. It begins as a waltz, then shifts to 2/4 time, and then returns to 3/4 time (Dillan 1970: no. 43). The name likely refers to this very feature—that the tune changes rhythm along the way and is thus “both and.”

From Soknedal in Midtre Gauldal in Trøndelag, there is an interesting legend about a woman named Gjertru. She came over the mountains to the village and settled by a waterfall, where she cleared land for a farm. She kept to herself and, in addition to farming, ran a smithy. Even when she was away from the farm—later named Foss—people could hear the sound of hammering on the anvil; it was rumored that she received help from supernatural beings both for this and for building the farmhouses. About Gjertru, it was also said:

“Gjertru was larger and broader than usual. Folk tales claimed that she was a boing.” (Haukdal 1974)

If Gjertru was a real person, she must have come to the farm in the late 1500s. What’s most interesting, however, is that the legend about her remained alive well into the 20th century. The connection between Gjertru being a båing and her contact with supernatural forces perhaps reveals something about how gender nonconformity was perceived in earlier times.

The existence of words like tvitulling and båing shows that there have been terms for various forms of gender nonconformity—phenomena that today might be categorized as intersex, trans, or—in some cases—homosexual or bisexual.

Dilldallmenn, Homos, and “Lesbian Love”

There is also a multitude of other words that have been used to describe gender and sexual nonconformity. While terms like homosexuality, bisexuality, fetishism, transvestism, and transsexuality were introduced into the Norwegian language through medical journals and textbooks in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, earlier terms such as sodomy and pederasty were used by jurists and theologians—and also had some popular usage. There were also folk expressions for sexuality between women; for example, the phrase daske fladkundt was used in a court case from Nordland in the 1840s (Skjoldhammer 2018, pp. 16 and 30).

The word homosexuality became more widespread during the 20th century, and shortened forms like homo and homse eventually came into use (Jordåen 2003: 110–111). A slang dictionary from the 1950s lists the following words for a homosexual man: sodagutt, bakstreber, soper, mannemann, dill-dallmann, and pipefeier (Gleditsch 1952: 37–38).

The terms lesbian and lesbian love were also used in medical literature from the late 19th century, but were less common than homosexuality (though some instances appear in newspapers from the 1920s onward). Homosexuality was for a long time primarily associated with men. The aforementioned informant from Hordaland, a woman born in 1927, explained that while men perceived as “effeminate” were called tvitullingar, it was different for women:

“The women we later suspected were homosexual behaved differently. They were called jomfruer (maidens). Homo and homosexual were words we only heard as adults. I had an aunt who worked at a knitwear factory. She lived with another woman until they were 80. They were so jealous of each other. They couldn’t stand one going on vacation without the other.” (Kristiansen 2008: 52)

Cultural scholar Tone Hellesund has shown in her research that middle-class women who lived alone or with other women were rarely interpreted through the lens of the new term homosexuality until well into the 20th century (Hellesund 2003). They might be seen as somewhat unfeminine, but these “old maids” were generally regarded as respectable women and not associated with the emerging vocabulary of sexuality.

In 1951, the Norwegian section of the Forbundet af 1948 (League of 1948) published its first brochure. Here, the organization’s mission was defined as “defending the human rights of the minority in society made up of people with a homo- and bisexual orientation toward love.” In addition, the term homofile (homophiles), already in use in Denmark and internationally in the gay rights movement, was introduced into Norwegian (Forbundet 1951). Although the term lesbian was not entirely unknown at the time, it seems that it was only with the rise of lesbian feminism in the 1970s that the term came into more frequent use (Taule 2017).

Also see Stian Hårstad’s article on the term hommann (courtier) – gutevoren gjentunge (boyish girl).

Minorities and Further Research

The terms that have been used tell us a great deal about shifting views on gender and sexuality over time, and closer studies of queer linguistic history can deepen our understanding of this. The words reflect power, prejudice, and changing perceptions of human sexuality. Most importantly, they show that there has long been an awareness that certain individuals could belong to categories outside the normative forms of gender and sexuality.

There are few sources that can tell us much about queer history in Norway before the mid-20th century, and this is even more true for national minorities and Indigenous peoples. In that context, it is interesting that, according to a 1945 dictionary of Rotipa (Norwegian Romani), there exists a word for “sodomite”—likely meaning a man who has sex with men: bykalar (Ribsskog 1945: 51). In a more recent dictionary, we also find the term gavo mors, translated as “homosexual” (Karlsen 1993: 30). As for Sámi, I am not aware of any equivalent historical terms, apart from bonju (queer), which has only recently come into use with this meaning.

A closer look at how words have emerged and changed in meaning could be an interesting contribution to the history of gender and sexuality. The purpose of this article has been to present some of the words and expressions I have come across in my research as a historian. For a deeper understanding, more systematic investigations are needed.

Literature

Bjørneboe, Jens. 1974. Haiene. Historien om et mannskap og et forlis. Oslo: Gyldendal.

Dillan, Helge. 1970. Folkemusikk i Trøndelag 1. Verdal i Nord-Trøndelag. Oslo: Noregs boklag.

Forbundet av 1948. 1951. Hva vi vil. Oslo: Forbundet av 1948.

Garborg, Arne. 1925. Dagbok 1905–1925. Band 2: 25. juni 1907–27. december 1909. Kristiania: Aschehoug.

Gleditsch, Ulf. 1952. Det får'n si. Norsk slangordbok. Oslo: Nasjonalforlaget.

Hamsun, Knut. 1930. August. Oslo: Gyldendal.

Haukdal, Jens. 1974. Busetnad og folkeliv i Soknedal. Gard og grend III. Støren: Midtre Gauldal kommune.

Hellevik, Alf. 1966. Norsk ordbok. Ordbok over det norske folkemålet og det nynorske skriftmålet. Band I: A–doktrinær. Oslo: Samlaget.

Hellesund, Tone. 2003. Kapitler frå singellivets historie. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Jordåen, Runar. 2003. "Frå synd til sjukdom? Konstruksjonen av mannleg homoseksualitet i Norge 1886-1950." Hovudoppgåve, Universitetet i Bergen.

Jordåen, Runar. 2010. "Inversjon og perversjon. Homoseksualitet i norsk psykiatri og psykologi frå slutten av 1800-talet til 1960." PhD-avhandling, Universitetet i Bergen.

Karlsen, Ludvig. 1993. Romanifolkets ordbok. Tavringens Rakripa. De reisendes språk. Kløfta.

Kristiansen, Hans W. 2008. Masker og motstand. Diskré homoliv i Norge 1930–1970. Oslo: Unipub.

Kvam kulturminnelag. 1993. Gamle ord og vendingar frå Kvam. Øystese: Kvam kulturminnelag.

Ordbog over det danske sprog, "Tvetulle", henta 21.02.2017, www.ordnet.dk/ods/ordbog?query=tvetulle.

Røthe, Eirik. 1994. Vossamålet i ord og vendingar. Voss: E. Røthe.

Ribsskog, Øyvin. 1945. Hemmelige språk og tegn. Taterspråk, tivolifolkenes språk, forbryterspråk, gateguttspråk, bankespråk, teng, vinkel- og punktskrift. Oslo: Johan Grundt Tanum.

Skjoldhammer. Tonje Louise. 2018. "Forargeligt og Uteerligt Forhold.Rettsforfølgelse av sex mellom kvinner på midten av 1800-tallet i Norge." Masteroppgave, Universitetet i Bergen.

Taule, Siv. 2017. "'Støtt de lesbiske i Kina og Albania!' Lesbiskfeministiske tidsskrift fra 1970- og 1980-tallet." Masteroppgave, Universitetet i Bergen.

Torp, Alf. 1919. Nynorsk etymologisk ordbok. Kristiania: Aschehoug.

Uppdal, Kristoffer. 1919. Stigeren. Tørber Landsems far. Kristian: Aschehoug.

ARCHIVAL MATERIAL:

The Regional State Archives in Kongsberg (SAK): Porsgrunn City Court, preliminary hearing protocol no. 1. (1890–1894).

Thanks to Torbjørn Steen-Karlsen, who tipped off the Queer Archive about the legend of Gjertru from Soknedalen.